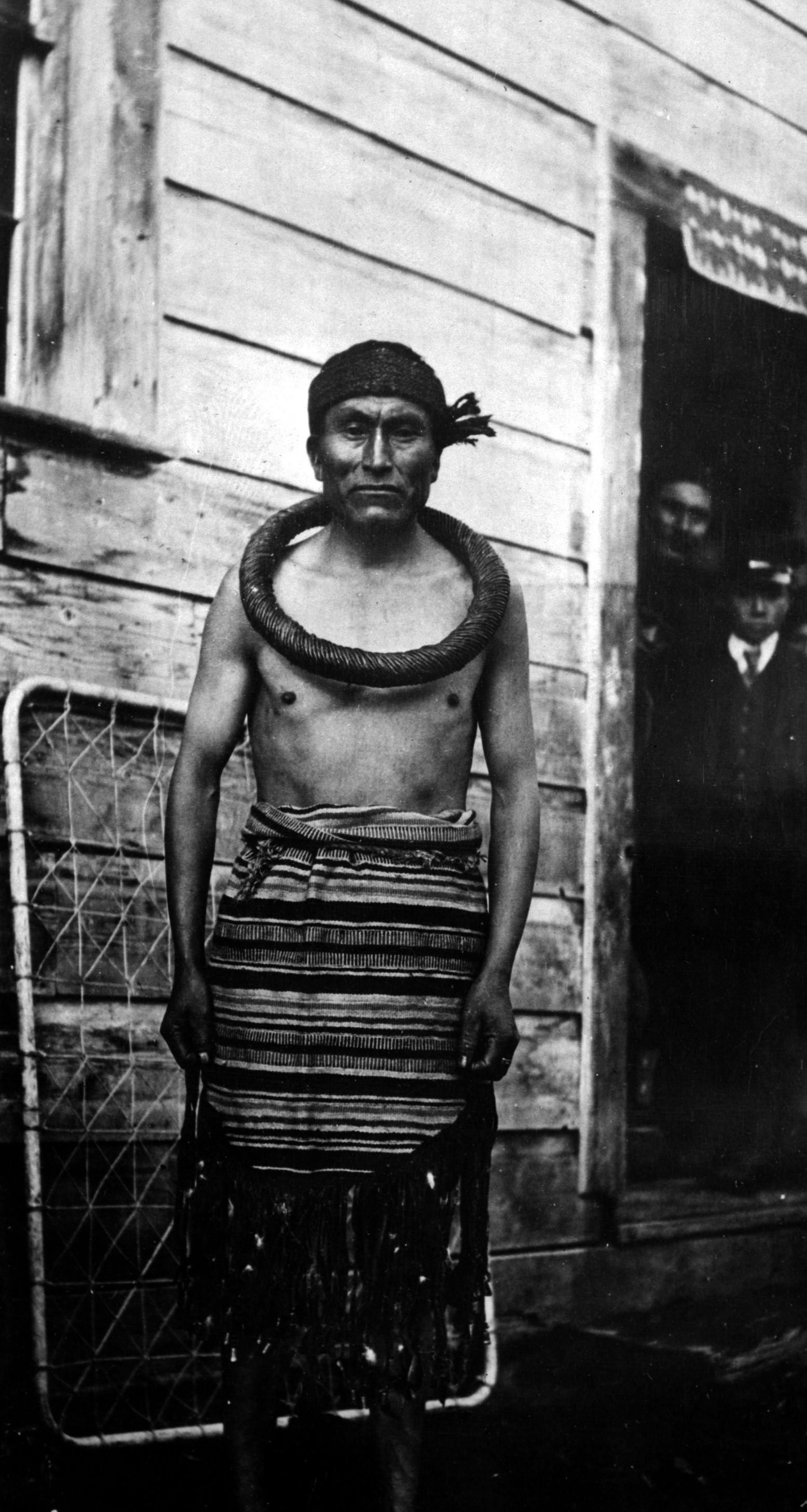

The lands in BC have been populated by the ancestors of First Nations since time immemorial. Oral Traditions across what has become British Columbia (BC) relate multiple Origin stories describing how the ancestors of BC First Nations peoples came into being. These stories often involve supernatural beings, animals and people in the founding of Tribes and lineages, as well as the creation of landforms and the foundation of customary law.

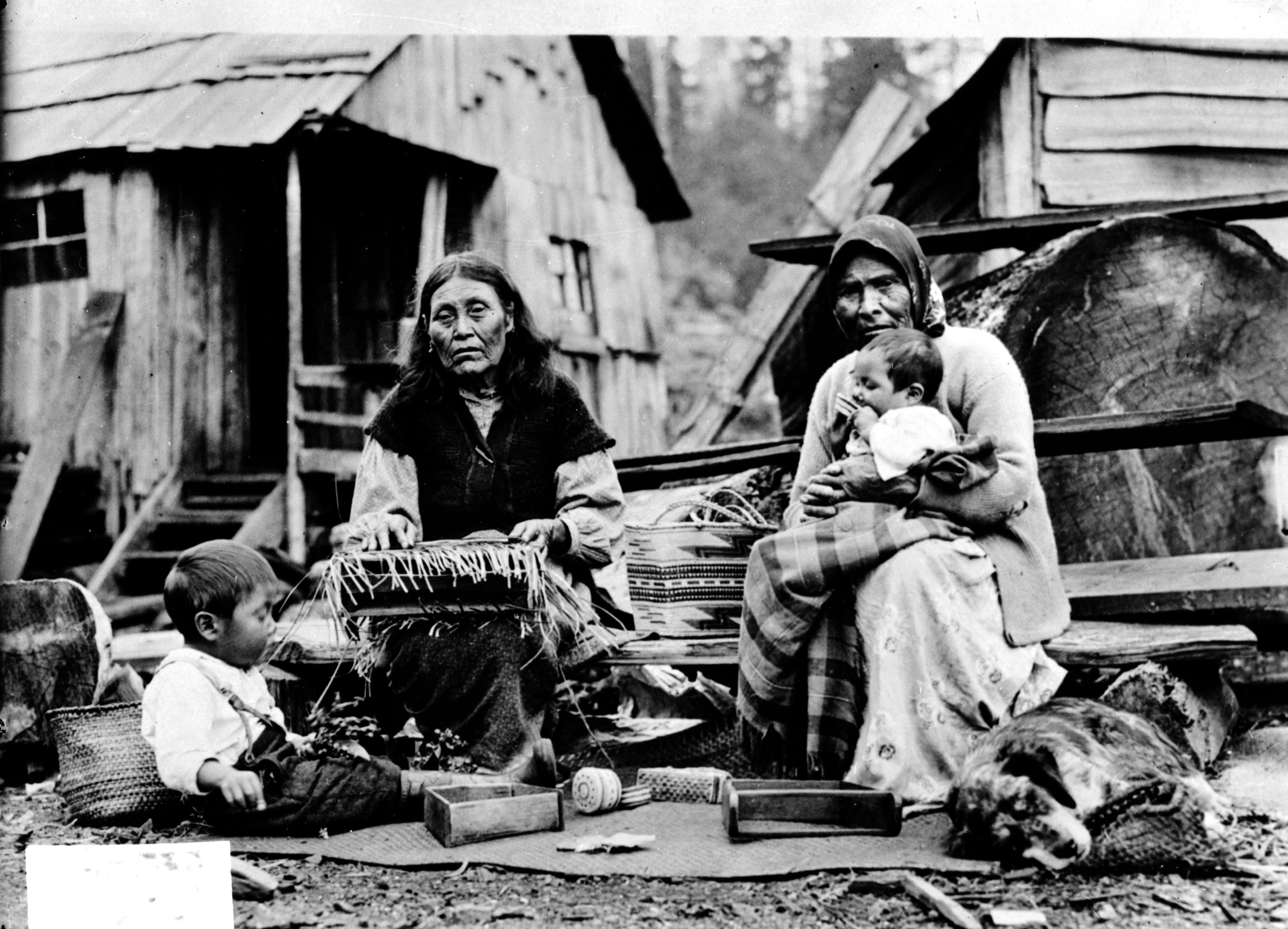

Varying according to region and culture, First Nations generally practiced a mix of hunting, fishing and gathering foods. Also, they manufactured goods from local and imported sources. Complex social and cultural institutions existed within these communities. Sophisticated methods of harvesting, management and preservation of the food were developed to handle the seasonal abundance of resources. These resources were carefully managed to ensure long-lasting abundance. Find additional resources on the Canadian Museum of History exhibit First Peoples of Canada.

Our 2010 video series and accompanying document

'Implementing the Vision - Reimagining First Nations Health in BC' provides a background on the driving force behind the work of the First Nations Health Authority.

First Nations have a complex health history. The first video in this series, "Implementing the Vision: Chapter 1 - System of Wellness" provides an in-depth background on this history.

First Nations Pre-Contact Health

In pre-contact times, First Nations enjoyed good health due to an active lifestyle and healthy traditional diets. These diets were balanced and included protein, healthy fats, and some fruits and vegetables. Oral history suggests good health and longevity. This good health included ceremonial, spiritual, and physical elements. Specific types of healers included midwives, herbal healers, and shaman. In addition, there were customary laws regarding food and hygiene that assisted the people in staying healthy.

Pre-contact lifestyles had many other “health-protecting” characteristics as well, including small size, comparatively low population density, reasonable mobility on land and water, seasonal relocations to different harvest locations, intimate knowledge of the local environment, environmentally friendly subsistence practices, and the availability of a variety of foods. As noted above, the hunting, fishing and gathering lifestyle ensured that people were physically fit. Although there were some health problems related to work, such as arthritis, prior to contact First Nations experienced virtually no diabetes and no dental cavities, though abscessed jaw sockets were common. Also there were some instances of First Nations people having a limited number of infectious diseases and dermatological problems.

Traditional Healing

The role of Spiritual Healers, also known as Shaman, was well understood in pre-contact times, and today as well spiritual wellness is considered a necessary part of whole health among First Nations in BC. Oral history and continuing practices confirm these deeply held beliefs. Throughout history there have been specialist healers who use plants to heal a wide range of ailments. First Nations throughout BC have developed intimate understandings of their environment and the healing qualities of many plants, some of which are also used during ceremonies and for other spiritual reasons.

Communities and families greatly valued holistic approaches for preventative health care. When a member of a community fell sick, the family and community would provide support and comfort, a practice that is as much in evidence today as it was in the past. A sense of place and belonging was recognized as one of the factors affecting health. Custom and wise leadership ensured that people had roles in their communities that took advantage of their particular skills, everyone contributing to the overall well-being of the group. In terms of child-rearing, it was commonly understood that children were raised and nurtured not only by their parents, but by their extended families too, especially grandparents, uncles and aunts. This ensured that the child’s growth and education was properly addressed by knowledgeable members of the family and community. First Nations communities thrived by working together to ensure their members were cared for so that the Nation remained strong.

Population Estimates

Prior to contact with Europeans, the area now known as British Columbia had one of the densest and most linguistically diverse populations within what is now Canada. It is estimated that one third of the pre-contact population of Canada resided within British Columbia. Pre-contact population estimates for BC vary widely with some estimates ranging from a conservative 200,000 to more than a million. Earlier estimates of 80,000 have now been discredited as far too low.

Oral traditions of many First Nations give a much higher original population than what is generally accepted by western academics, even now. From oral history and ongoing research it is clear that the European diseases that ravaged the Central and South American populations spread in advance of actual contact to First Nations in BC. Therefore early explorers and traders who considered the populations quite low were witnessing Nations who had already experienced drastic decreases. What is clear to everyone is that the population was of ancient origins, large, varied, and relatively healthy prior to the introduction of European diseases.

Contact

Contact between First Nations and non-Aboriginal people occurred rather late in BC, some of the earliest recorded contact occurring in the late 1700s with Russian, French, Spanish and British traders and explorers all visiting parts of the coast during this time. Inland contact was primarily through traders (Hudson’s Bay Company) and explorers (Alexander McKenzie and Simon Fraser). It is also possible that other earlier unrecorded contact occurred on the coast.

Population Collapse

Epidemics spread through First Nations communities in advance of explorers. Some researchers have suggested epidemics reached the Northwest Coast as early as the 1500s, believing the well-known epidemics from the Caribbean and Central America may have spread to the Pacific Coast through native trade networks and social contact. Some of the recorded epidemics in the Interior were known to have originated on the prairies during the historic period (early 1800s). The introduction of infectious diseases from Europe and Asia into the Northwest Coast and adjacent areas, and an increase in the severity of warfare, had devastating effects on the people.

Lacking biological or cultural adaptations to these diseases, First Nations were overwhelmed. Smallpox, influenza, measles, and whooping cough were recorded epidemics, with smallpox particularly recurring with devastating effects in the native population. In some cases, people who were sick may have otherwise survived if provided with basic care. First Nations health systems had never encountered these diseases and were unprepared to deal with them. These epidemics continued throughout the historic period and caused ongoing and dramatic population decline. When these epidemics struck, people died in such mass numbers that it was a common occurrence for bodies to remain unburied.

With so many people affected by these diseases, at times regular food harvest was impossible. The disruption in harvesting during these times made matters worse with a lack of available food for the remaining tribe members and further reduced their immune systems’ resistance to disease due to lack of nutrients. Chronic diseases also entered the population at this time and included Tuberculosis and venereal diseases. It is clear that in some cases entire villages were significantly reduced in single disease events, with mortality rates ranging from 50% to 90% of the population. During this time there was a vaccine for smallpox, which was discovered in Europe in the late 1700s; however it was rarely provided to First Nations people.

Without a written culture, First Nations lost large pieces of their oral knowledge when experts died off in large numbers during the epidemics. The population collapse seriously unbalanced traditional health care systems. These new diseases overwhelmed and infected the traditional healers themselves, while simultaneously discrediting their methods when they proved ineffective against new maladies. Healers were nearly powerless in the face of the new diseases. During this time, the smallpox epidemic undermined the power of many coastal First Nations, clearing the way for the colonization and repression that followed. The concept of terra nullius, or settlement of ‘empty land’ was advanced at this time, based on the recently depopulated landscape that resulted from these waves of epidemics.

Our 2010 video "Implementing the Vision: Chapter 2- A Knowledge Gap" examines the effects of residential schools and the forces of colonization. These forces are examined in relation to First Nations health.

Colonial Period

Following the population collapse, governments and churches sought to actively colonize and control the newly weakened First Nations. Colonial authorities were expanded to facilitate land and resource extraction, and to limit First Nations rights. Indigenous spirituality, political authority, education, health care systems, land and resource access, and cultural practices were all repressed. In some missionary writings there are explicit descriptions of attempts to eradicate traditional healing practices.

Later on, residential school systems were established to remove children from their First Nations communities with the aim of assimilating them (see more about these below). The myth of the dying First Nation society was used to justify political action that benefited non-aboriginals at the expense of First Nations. BC was one of the more xenophobic colonies of the British Empire; the nineteenth and twentieth century anti-Chinese and Japanese legislation, union organization, racially-based and segregated work division, and race riots further demonstrate the sustained discrimination and the single race (Caucasian) aspirations of the time.

The Indian Act (1876) provided the following dictates for First Nations Health: "The Governor in Council may make regulations

- to prevent, mitigate and control the spread of infectious diseases on reserves, whether or not the diseases are infectious or communicable

- to provide medical treatment and health service for Indians

- to provide compulsory hospitalization and treatment for infectious diseases among Indians.

(More complete information about the Indian Act compiled by the Parliamentary Research Board).

The 1918-19 influenza pandemic was the last major epidemic to seriously affect First Nations and marked the end of the epidemic cycles that had begun over 150 years previously. As the 20th century proceeded, First Nations populations reached their low point and then slowly began to rebound. At the same time government and church control over the Indigenous population reached their high points.

Impacts of Church and State

As epidemic diseases declined, endemic disease and other health issues arose. Tuberculosis became an even more widespread problem and dental health deterioration became an issue as well. Diets were changing to include more starch and processed sugar and alcohol use became more widespread in our communities. Churches and government exerted even greater control over First Nations health during this time, due in great part to the loss of control over First Nations’ traditional health systems. The repression of cultural practices with shaman and even herbal healing by western doctors meant that Services were limited and often of low quality, and sometimes western health services were denied to First Nations entirely.

Residential Schools

Residential schools had high rates of tuberculosis, high mortality rates (especially early in their history), and poor quality food. These schools were funded by the federal government and run by many different church denominations. A high rate of physical and sexual abuse was present in these facilities. Also, there were some cases of children being involved in medical experiments and incidents of severe punishments that sometimes resulted in death. The ongoing residential school assimilation policies disallowed First Nations children from speaking their languages, as both church and state sought to disconnect the children from their cultural practices. Sick children were kept in the schools in the same facilities as other children, spreading by disease both within the schools, and to the communities when children were eventually sent home during their last days. Mary-Ellen Kelm writes “scores of residential school children were discharged because they were not expected to live. This strategy was intended to achieve humanitarian and practical ends. It allowed the family to spend some time with the child before the child’s death, and it meant one less death to be investigated at the school.”

20th Century Health Care

During the twentieth century, First Nations were in a state of massive change. With populations at an all-time low and military strength severely disrupted, First Nations retained virtually no political power in the face of the repressive Canadian legislation. This resulted in social disruption of the existing First Nations health care systems, damage to traditional belief systems, and a decrease in orally-held knowledge. As discussed, new pathogens were wreaking havoc with First Nations health at this time, which combined with the displacement from territory and resources resulted in poverty, reduced food security, and crowded living conditions, all contributing to poor health outcomes. However, some traditional healing continued and even non-Aboriginal people availed themselves of these services, especially in areas with no regular access to western medicine.

Midwives continued to practice in many areas, partly due to lack of access to western services but also because of First Nations resistance to western medicine. Doctors argued for western medicine to oversee childbirth, but the federal government opposed paying for western medical care for First Nations women. Western medicine was only sporadically available; it was seldom of the highest quality and largely segregated. Little if any western medical care was available to First Nations to deal with tuberculosis until the 1940s, even though there was an extremely high rate of First Nations people affected by tuberculosis before this time.

Discrimination was overt and widespread. Social segregation of the kind often associated with the American south was a common feature in BC during this time. During the early 20th century, separate “Indian hospitals” were established to treat First Nations peoples with certain diseases such as tuberculosis. The “fear of interracial pathological contagion” likely provided the greatest motivation for the development of separate services for First Nations.

By the early-20th century, the spread of tuberculosis, in particular, was causing much anxiety. Between about 1912 and the mid-1930s, government and health officials debated whether to establish separate facilities for Aboriginal people suffering from the disease. In the meantime, a few hospitals opened wards for Aboriginal people with TB, but, overall, treatment facilities were few and far between. In the mid-1930s, the Cooqualeetza Indian Hospital was established in Sardis, B.C. and served as the primary First Nations sanitarium for a decade. In the mid-1940s, Indian hospitals also opened in Nanaimo and Prince Rupert. Medical practitioners who worked with Aboriginal peoples had advocated in the 1920s for more facilities closer to where people lived and where their families could be involved in their care. The system of hospitals that was established instead had the opposite effect, separating families by large distances, both emotionally and physically.

Population Rebound

As epidemic diseases became less common, First Nations populations rebounded dramatically. Villages that had been previously been reduced to a mere handful grew quickly as infant mortality fell, life expectancy started to increase again. Today, First Nations are one of the fastest growing populations in Canada. Birth rates are high, the population is young (estimates are that half the First Nations population is under 25) and it is anticipated that the population will continue to grow into the future at much higher rates than other British Columbians.

A Changing World

World opinion began to change during the 20th century. World War I reduced support of the political status quo, with changes to women’s rights and the role of religion in society. Following World War II, colonial powers were severely weakened and independence movements in Asia and Africa began to gain strength. The Indian (British India) nonviolent resistance movement, Cold War activities and propaganda, and the United States civil rights movement strongly influenced the shift of governments away from maintaining overtly repressive systems. In 1951 the Canadian government quietly dropped some of the more repressive sections of the Indian Act including bans on cultural expression, political agitation, and segregationist policies. First Nations obtained the right to vote in Canada in 1960 having received the provincial vote in 1949.

In 1969, the federal government produced a white paper which advanced a policy of formally assimilating Aboriginal people in Canada, removing any ‘special rights’, dissolving the reserve system, and ending the separate legal identity for Indians. Viewed as a final assault in First Nations identity and culture, the reaction to the 1969 white paper was the birth of modern First Nations political activism.

Following the rise of First Nations political activism, a series of legal cases, social changes, and decreasing direct control ensued. Direct missionary control was reduced or eliminated in most communities, and First Nations began to assert more control over governance and education, culminating in the end of the residential school system, an increase in political authority in limited matters, and, in 1982 the protection of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Canadian Constitution.