Introduction

Children are cherished as sacred gifts from the Creator and recognized as both the present and future of First Nations families, communities and Nations.

Each child is seen as part of what makes a family and community whole. Their nourishment and protection is a central focus – and the health of the entire community is reflected in the health and happiness of its children.

BC First Nations have always known that childhood is a unique and precious time in a girl's growth and development. The connections that girls establish during these early years, their environments and how their bodies are nourished all have an impact on their future health outcomes.

Girls are defined in this chapter as being between the ages of one and 12, although the ages captured by some of the quantitative data sources differ slightly. Download a pdf of this chapter.

“We have been caring for our children since time immemorial. The teachings of our values, principles and ways of being to the children and youth have ensured our existence as communities, Nations and peoples. The values of our people have ensured our existence. It is to the children that these values are passed. The children are our future and our survival." – Shuswap Elder Mary Thomas

Roots of Wellness

Connections to culture and the ancestors, language and ceremony • Connections to land • Connections to community

A healthy childhood is pivotal to establishing the roots of wellness for First Nations girls.

The individual identity that each girl forms through connections to culture, the land and the community provides a foundation for health and well-being throughout her life. When these connections are strong, girls grow up with an understanding of where they come from, where they belong in the world and how to live in a good way.

“When we teach children our traditional values, we stay connected to our ancestors. This makes children some of our most powerful teachers and healers." – Children's Voices, Our Choices

Promising Practice

The Grandmothers' Group of the Northwest Inter-nation Family and Community Services Society (NIFCS) are majority matriarchs of the nine tribes of Lax kw'alaams.

Brought together around their traditional matriarchal teachings, Lax kw'alaams grandmothers support children and families in ensuring children stay connected to their community, heritage and culture. They do this by inviting children and youth to meet their extended families in Lax kw'alaams and to learn cultural activities such as traditional seaweed gathering.

They help to promote healing for families in the community and, in doing so, have reduced the number of children being taken into care.

“We are here to support children and families, to work with our children and youth, to encourage them to complete their education, to take pride in who and what they are, where they come from, to teach them about their culture, who they belong to—their Nation, tribe, crest, clan, family—to help work towards and build self-care plans and safety plans so that our children feel safe—and parents as well.

We're here to be mentors and role models and helpers and teachers." – Grandmothers' Group

Supportive Systems

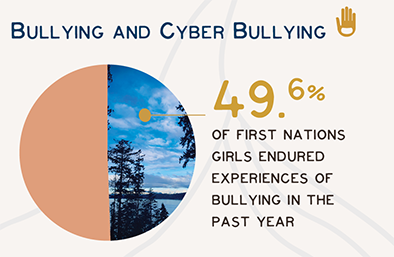

The ongoing legacies of colonialism – racism and discrimination, violence and abuse, bullying and cyberbullying, and intergenerational trauma • Systems – education, economic, food, health, child welfare

Teachings passed down from Elders and Knowledge Keepers serve as a reminder that children are the hearts of First Nations families, communities and Nations. The care of children is a "sacred and valued responsibility" (Early Learning and Child Care, Assembly of First Nations) and cultural values and practices help to ensure that girls have strong systems of support around them, enabling them to flourish.

At the same time, many of the systems that First Nations girls and their families must interact with to meet their basic needs – systems for education, food security, housing, health, justice – remain rooted in colonialism and continue to create and perpetuate racist barriers that disadvantage First Nations girls and influence their social determinants of health.

BC First Nations girls are following the lead of their strong, resilient matriarchs. They are adding their voices, perspectives and wisdom to this work to reclaim and transform systems, attitudes and relationships in ways that are necessary for creating environments in which all First Nations girls are supported in thriving and living to their full potential.

“I hope that the next generation grows out of this racism and ignorant phase and grows a healthy bond and place where everyone gets along and is respectful with each other." – Natasha, Ojibwe and Irish, and an intergenerational residential school survivor

Promising Practice

Haley Paetkau organized the first Orange Shirt Day to be held at her school, in Victoria. She was inspired by seeing her father, Steve Sxwithul'txw, share stories at an Orange Shirt Day ceremony held to help educate people about the impacts of residential schools on Indigenous families.

“If we know about the past, we can try to make it better in the future. That residential school is something, yes, that happened and Orange Shirt Day is a time to try and educate more people." – Haley Paetkau, Penelakut First Nation

Healthy Bodies, Minds and Spirits

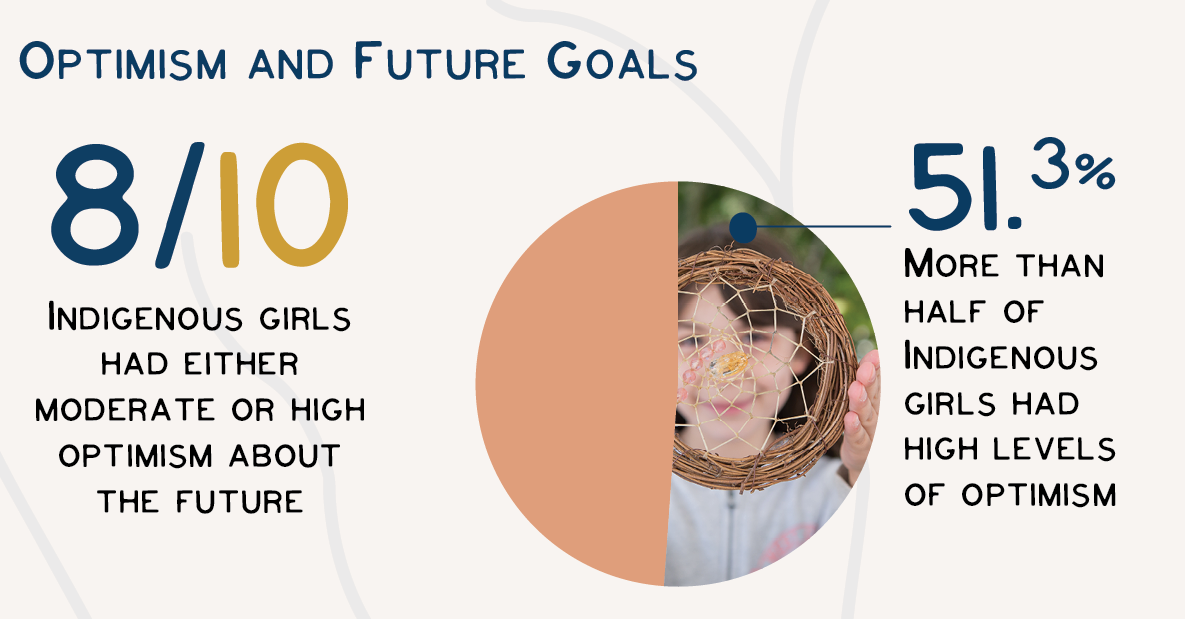

Body image • Happiness • Healthy eating • Mental wellness • Optimism and future goals • Oral heath • Peer relationships • Physical activity • Physical disabilities or illness • Screen time • Self-esteem • Self-rated body weight • Sexual well-being • Sleep

First Nations girls live, grow and flourish in the context of their families and communities.

Mental, physical and spiritual wellness is strengthened by identity, culture and kinship ties. Conversely, it is negatively impacted by intergenerational trauma, systemic racism and discrimination. The health outcomes for First Nations girls are shaped by their physical and social environments as well as the cultural values that underlie their lifestyles, behaviours and relationships.

“Remembering who we are is absolutely important as we look forward to who we want to be again in the future – as nations, as families, as communities.

We have … a vision that speaks to healthy children, healthy families and healthy communities, but also having a sense of vibrancy. And what does vibrancy mean? How do you measure vibrancy? Our Elders said, it starts with the sparkle in the eye of a child. Do our children have a sparkle in their eyes? What does that actually mean for a child to have a sparkle in their eye? It's a sense of belonging, a sense of love, a sense of purpose, a sense of safety. It's being inquisitive – wanting to know things." – Gwen Phillips, Ktunaxa Nation

Promising Practice

The Indigenous Sexual Well-being Learning Model has been used by some communities to start conversations around traditional knowledge and ways of being in regards to healthy sexuality.

The model is a strengths-based one that acknowledges healthy sexuality as an important aspect of overall wholistic health and wellness. The model builds on First Nations values related to developing and maintaining healthy relationships and protecting oneself and one's community from communicable diseases, including sexually transmitted infections.

Being immunized for HPV is a particularly important way girls can care for themselves and help protect their future sexual well-being.