Introduction

In First Nations communities, the birth of a baby is a sacred event to be joyously celebrated.

Each Nation has distinctive teachings, knowledge and ceremonies that surround each phase of the journey, from preconception through pregnancy and childbirth. Women are honoured and accorded special respect for their role as life-givers, which is seen as a tremendous gift.

Today, although First Nations mothering occurs within the context of historical and ongoing colonial policies and practices, many Nations and matriarchs are actively sharing their traditional teachings and restoring their customs and many First Nations parents and their infants continue to benefit from them.

This chapter focuses on health and wellness during the perinatal phase (from conception through childbirth) and the postpartum period. It considers the well-being of infants and mothers (those who are biological mothers and those who play a role as mothers in their communities). Download a pdf of this chapter.

“When I had my first child, I had my grandmother, my aunts, my mom – I had a lot of important women in my life attend the birth. Because birth is such a celebration for our people that everybody shows up and it's kind of difficult because it's limited in a maternity room when you want to have all these special women in your life be there to celebrate the birth and be there for support." – Jodi Payne, Tahltan Nation

Roots of Wellness

Connections to culture and the ancestors, language and ceremony • Connections to land • Connections to community

Restoring choice, control and self-determination of First Nations women and communities is key to ensuring that First Nations mothers, babies and families are vibrant, healthy and able to thrive.

Reclaiming First Nations teachings and protocols around birth, pregnancy and mothering helps to strengthen vital connections to land, culture and community.

These connections, which are the roots of wellness at all phases of life, help to nurture the wholistic wellness of women during the transition to motherhood while also establishing a strong foundation for infant health.

“During a baby welcoming ceremony, there are roles for cultural speakers, a coordinator, family and witnesses. The family places blankets and headbands on the cultural speaker and coordinator to protect their minds during the ceremony so that they will only give good thoughts to the young child and family. The blanket protects their hearts so that they will only have good feelings for the baby and family.

The family places the baby on a new blanket on the floor or ground and stands over the baby. Another family member cares for the baby.

Witnesses are called upon to share what they have learned about welcoming the new baby and their responsibility to always keep an eye out for the child throughout the child's life. The witnesses also share with the family their teachings on bringing a baby into the world and they pass this information along to the new family." – Lucy Barney, Titqet Nation

Supportive Systems

Culturally safe, trauma-informed perinatal care • Equitable access to culturally appropriate health care and supports • Birthing closer to home • Restoring First Nations midwifery practices

The social determinants of health and wellness of First Nations mothers and infants are shaped by the wide range of systems mothers must interact with to meet their basic needs, including systems for health, education, food, housing and justice.

Because of historical and ongoing systemic anti-Indigenous racism, many First Nations women face barriers to establishing safe environments for themselves and their infants and accessing their basic needs around education, health, housing, employment and food. As a result, First Nations women are more likely to experience poverty, food insecurity, violence and unsafe living conditions.

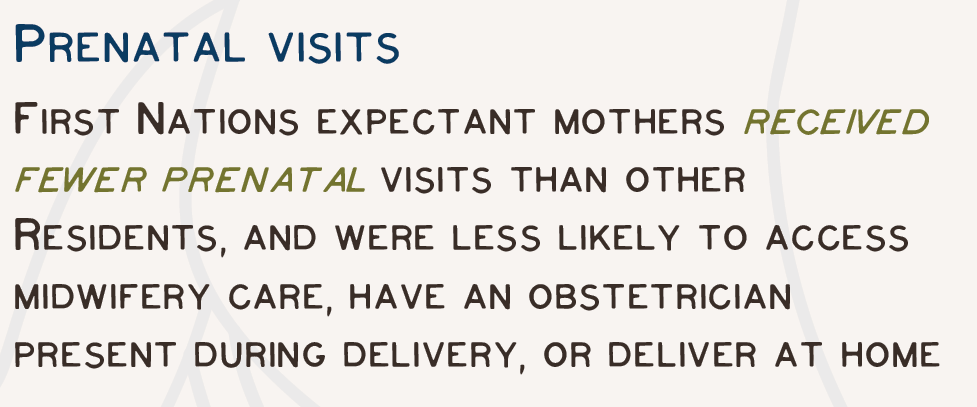

Mainstream systems have also adversely impacted individual and collective experiences of childbirth for many First Nations women. The health system is particularly influential in shaping the prenatal experience, childbirth and postpartum recovery.

“I moved to Nanaimo in June 2019 and gave birth to my daughter at the Nanaimo General Hospital shortly after. I had to stay there for four days, which was really terrifying for me because I was aware of birth alerts and aware of the overrepresentation of Indigenous children and youth in foster care. I even had it in my birth plan. As a visibly Indigenous person with an Indigenous partner, this was something we needed to be aware of as something that happens to Indigenous families all of the time.

I really only felt shielded by my non-Indigenous mother who was with me the entire time I was at the hospital ... I couldn't fully verbalize the fear that I was feeling, but I had this beautiful moss bag made for my daughter. I felt fear of bringing that moss bag to the hospital – just for fear of being judged and also because the nurses were so clear with me that babies weren't to be swaddled anymore so that was just an example of me wanting to bring in my culture into the hospital setting but not able to do so because of the fear." – Anna McKenzie, Opaskwayak Cree Nation, currently living on the unceded homeland of the Snuneymuxw First Nation

Promising Practice

The Kwakwaka'wakw Maternal, Child and Family Health Program is an initiative in the northern region of Vancouver Island that supports First Nations women along their pregnancy journeys, providing culturally safe care that is trauma-informed and woman-centred.

Working with birthing parents and their families, the program also helps to bring births closer to home – whenever possible – through a partnership with two local midwives.

For those women and their families who need to leave the region for maternity care, the program helps to ensure a seamless, coordinated and collaborative care experience.

Women and families can self-refer or be referred to the program by on-reserve services, family members, health care professionals or other agencies.

Contact: kwakwaka'wakw.maternity@fnha.ca

Healthy Bodies, Minds and Spirits

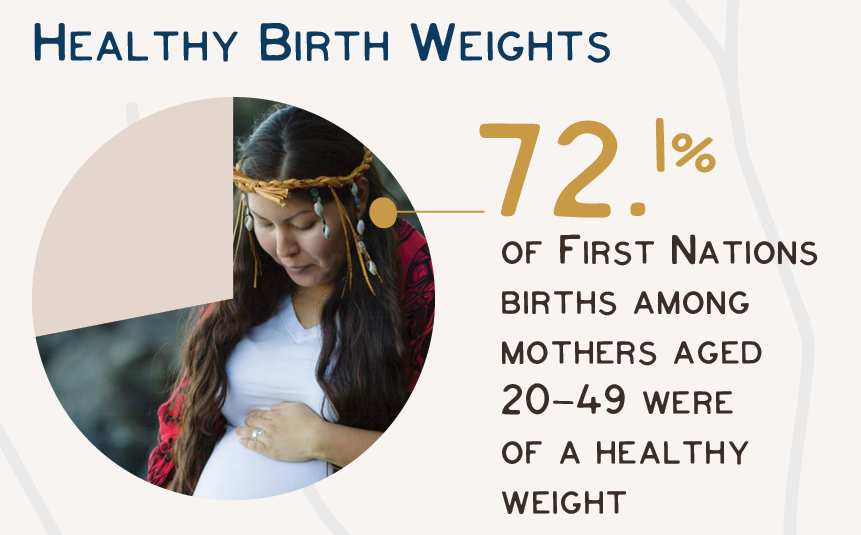

Eating well and staying active • Mental wellness and nurturing the spirit • Commercial tobacco, alcohol and substance use • Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder • Sexual well-being and reproductive justice • Healthy infants

First Nations perinatal practices, ceremonies and traditions around care have always sought to promote the wholistic health and well-being of both mother and unborn baby. They are intended to instill a strong sense of responsibility for ensuring health throughout pregnancy, labour and infancy by striving for balance in all aspects of life – physical, mental, emotional and spiritual.

However, pregnancy can also be a very stressful time, particularly when it is unplanned or when the expecting mother is already living with health, social and economic challenges.

Reconnecting to First Nations teachings around pregnancy can help to remind women of their inherent power as life-givers. Positive, supportive relationships are also vital during this time.

“I am expecting my first baby, so I don't have any of my own stories for my own babies. I made some tiny jars of half-smoked moose without any additives for my sister to use for baby food and my nephew ate three jars in a row at one year old! Baby born from the land. Moose stole his heart and fed him what he needed. Our baby foods have been providing the nutrients we need since time immemorial." – Willow Thickson, Michel First Nation, living in BC

Promising Practice

Greg Barry (she/her) of the Syilx Nation creates baby boards using practices passed down from the women in her family.

Referred to in some Nations as cradleboards, the boards are made from fabric, traditional buckskin or red willow boughs and a thin board. The baby is then secured by the board through the lace-up front.

Greg now creates baby boards for other families and is seeing growing demand for them as more people seek to bring back this beautiful custom.

“We grew up in baby boards and I knew that I wanted to carry on this tradition with my kids … My mom and my sister came to visit me and my mom brought an old board from a family member so we could see how it was put together. We worked together to make my daughter's board … It holds a deep sense of culture and tradition that you can feel when a baby is in their board … You can almost feel the presence of generations of ancestors when you see how peacefully content your baby is." – Greg Barry, Syilx Nation